Eliza’s Story

My Turn: Happy Birthday, Eliza Hamilton

by Thomas Henry Haines

In my earliest memory, I’m standing in front of the orphanage facing across the Hudson River to the Palisades, looking at a gorgeous sunset. I’m reaching up, holding somebody’s hand. It was August 1937, and I’d just turned four years old.

Two years earlier, my father had abandoned my mother. Living on welfare and left alone with a toddler in a Greenwich Village apartment, my mother suffered a nervous breakdown. On May 3, 1937, at the determination of a judge, I was committed to the Edwin Gould Foundation for Children “by reason of the insanity of the mother.” Three months later, I was sent to the Graham School, an orphanage in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York.

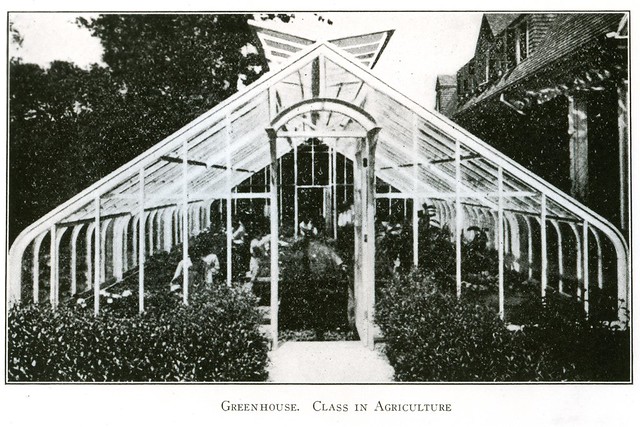

Most people imagine orphanages as cold, harsh, Dickensian institutions. But Graham was nothing of the sort. Situated on the crest of a hill overlooking the river, the Graham School resembled a college campus, with stately Federal-style brick buildings bordered by fields and farmland. In the center was a playground and the administration building, surrounded by a circular road leading to twelve cottages. Four girls’ cottages overlooked the Hudson River and the Palisades, and eight boys’ cottages were inland, where there was a farm with horses, chicken coops, and greenhouses.

Each cottage was like a family. The older kids looked after the younger ones, helped maintain the house, and kept things running smoothly. All the kids, depending on their age and abilities, were assigned chores, supervised by the housemother. I learned to cook, bake, run the boiler, and stoke the coal furnace. I learned to be responsible. If it was your turn to stoke the furnace and the cottage became cold, everyone would be mad at you. I learned all the skills I would need to make my way through life. Not just specific skills like gardening and plumbing, but how to take initiative in any situation—how to recognize opportunities and jump in without hesitation. These skills would later prove essential in my work as a scientist and educator, and also equipped me to find creative solutions to problems. For example, I invented a soft compression suit made from the fabric NASA used for astronauts’ space suits that allowed my first wife to live a normal life for as long as possible as she battled emphysema. I also helped found the Sophie Davis School of Biomedical education—a low-cost, six-year medical college that enabled underprivileged students to pursue careers as doctors—which later became CUNY Medical School.

Growing up at Graham, I never felt deprived. There was a warm and lively atmosphere, people were kind, and we never lacked for anything. On Saturday nights, we went to the local movie theater to watch Charlie Chaplin and the Marx Brothers. In the summer, we went swimming, and in the winter, we went cross-country skiing in the woods. For a few weeks each summer, I went to a camp in the Pocono Mountains in Pennsylvania, where I learned about the carnivorous swamp plants—pitcher plants and Venus flytraps—that I’d find and bring home and feed with bugs: a fascination with the natural world that foreshadowed my enduring interest in biology. Holidays were festive, with a Christmas carol competition around the big tree, and presents for every child. Every New Year’s Eve a group of us would go to lower Manhattan to take part in Audubon’s annual bird census. How many kids get to do that?

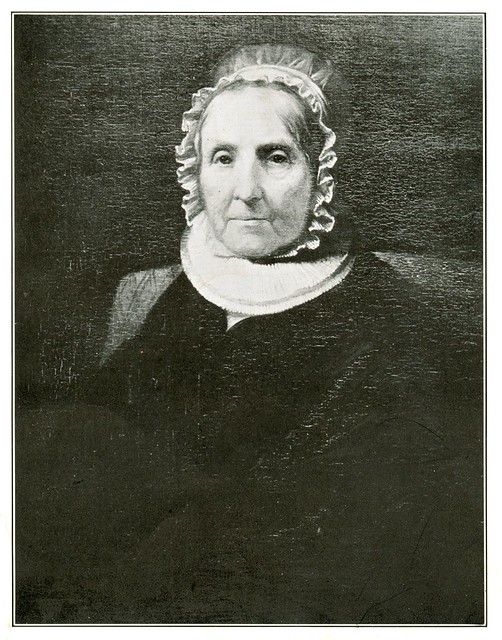

Framed portraits of the school’s founders, Isabella Graham and Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, hung in the administration building. As a child, I was familiar with the faces of the ladies in the oil paintings. But it wasn’t until I got a little older that I became aware of the school’s historic roots.

In 1806, Mrs. Isabella Graham, president of the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children, needed help caring for six children whose widowed mothers had recently died. She enlisted the help of her recently widowed friend, Eliza Hamilton, whose husband, Alexander Hamilton, had been killed by Aaron Burr in a famous duel two years before.

Eliza knew the hardship her husband had suffered as the orphaned child of an unwed mother. In addition to raising their own seven children, the Hamiltons had adopted a daughter and opened their home to other orphaned or neglected children (Eliza called them “little Alexanders”). Eliza joined forces with Mrs. Graham and other prominent women to create the Orphan Asylum Society in the City of New York—the city’s first private orphanage, located in a two-story Greenwich Village townhouse. From there, the orphanage moved north twice before settling into its current location in Hastings, NY, where I grew up.

On August 9th, I will turn 86. Only recently did I learn that Eliza Hamilton, the serious-looking lady in the oil painting, was born on the same day in 1757. This year on our shared birthday, it’s my turn to express my gratitude. Without Eliza Hamilton and Isabella Graham, who knows what my childhood—or the rest of my life—would have been.

Graham has since grown from a residential school to a family support and youth development agency that works with thousands of New Yorkers each year. As the only alumnus to serve on Graham’s Board, it’s my turn to give back. Not just through philanthropy and mentoring others, but by putting into practice the question my housemother at Graham taught me to ask myself every day: “What nice thing can you do for someone today?”

If someone reading this takes away just that, I will have even more reason to celebrate this birthday. I’m sure Eliza would be proud.

Oil portrait of Eliza Hamilton by Daniel P. Huntington

(Courtesy of National Museum of American History)

The late Thomas Henry Haines was a visiting professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Rockefeller University. Since 2007, Dr. Haines was a professor emeritus of chemistry and biochemistry of City College of the City University of New York. In the early 1970s, he worked under City College President Robert E. Marshak to establish the Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education, where he taught biochemistry for thirty-five years. Dr. Haines served on the Graham Board of Directors for 11 years. More about Dr. Haines can be found online: https://thomashaines.org and you can find his autobiography, A Curious Life: From Rebel Orphan to Innovative Scientist, on Post Hill Press.

Click here to learn about Graham’s history.